Government demolitions have displaced hundreds of thousands of people in Abuja, Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory since the early 2000s. While this is neither unusual in Nigeria nor in Africa more generally, Abuja is the fastest growing city in West Africa and its unusual property laws and the potential for unrest warrant greater scholarly attention. In “I am Here Until Development Comes: Displacement, Demolitions and Property Rights in Urbanising Abuja,” published in African Affairs (July 2014), anthropologist Josiah Olubowale and I argue that this housing insecurity is not simply the result of urbanization, population growth, or wealth disparities. We attribute it instead to a property rights

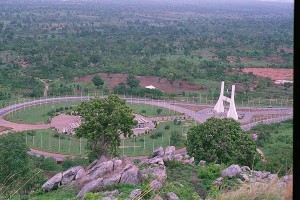

A picture I took of Abuja in 2000, from atop the high hill next to the city gate. Most of these areas are now developed.

regime that perpetuates discrimination by providing special land rights for the area’s early inhabitants. We also show how, as indigenes have been short-changed by policies to relocate and compensate them, their interests have aligned more closely with migrants seeking improved housing security. By pursuing the shared goal of housing rights for migrants and indigenes alike, new coalitions — both within particular slums and across them — have helped defuse tensions that could otherwise be conducive to conflict.

Organizations working for housing rights in Abuja’s slums include: Women Environmental Programme, the Social and Economic Rights Action Centre, and the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions.

We describe the origins of Abuja in the post-civil war policies of Nigeria’s military regimes, which sought to both integrate the nation and insulate the government from popular pressure centered in the coastal city of Lagos. Next, we integrate research from urban studies with literature on civil society, property rights, and civil conflict. This multi-faceted perspective sheds light on the persistence of a seemingly inefficient (and arguably unjust) land law, and demonstrates why the cooperation we documented runs counter to common expectations in social conflict research. We then describe how various governments adopted policies that generate incentives for indigenes to refuse resettlement, and to profit from

migrants. What can residents do to protect their rights? We describe residents’ strategic repertoire for responding to housing demolitions and the rise of new housing rights networks based on an alignment of interests between indigenes and migrants. Tenants and many indigenous landlords have come to share a common narrative of victimhood stemming from Abuja’s housing laws. We conclude that insecure tenancy gives Abuja’s poor no incentive to improve properties and note with concern the role of large estate developers. In the words of indigenous activists, ‘When development comes’ it brings displacement and disempowerment.