Guest Post By Jean-Baptiste Guiatin

American University

Since its inception, Burkina Faso’s transition has been facing tough challenges, some of which are of its own making. However, the international community should help save it for three reasons. First, supporting the caretaker government will give Burkina a new democratic start, and the youth a new reason to hope. Second, supporting the caretaker government will help maintain Burkina’s stability, thereby facilitating the fight against terrorism. Finally, the international community should support the Burkina transition because it is good for investment and business.

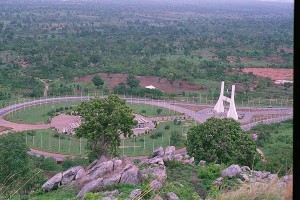

Located at the heart of West Africa, Burkina Faso is a country of 274,200 square kilometers with a  population of more than 15 million. A former French colony, it gained its independence in the 1960’s along with its neighbors such as Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Togo, Senegal, and Benin. As was usual in 1970’s and 1980’s in Africa, it took a turn for a Marxism-Leninism in the mid-1980’s with a group of young military officers led by Captain Thomas Sankara at its helm. In 1987, Sankara lost his life in a coup that brought Blaise Compaore, his right-hand man and second in command, to power. From that moment onwards, Burkina Faso started its long journey to liberalization, both politically and economically. Compaore’s three decade rule with explicit and implicit support from the West came to end in October 2014 when huge demonstrations of young people apparently led by well-organized civil society groups and opposition parties took place in the main cities. The main reason for this protest was Compaore’s willingness to modify the Constitution for a fifth term. A provisional government was quickly put in place to be in charge of the transitional process which should lead to presidential and legislative elections in October 2015. After almost ten months, this provisional government is sailing through troubled waters; its difficulties being so many that observers wonder if it will survive: high social demands, voting of controversial electoral rules, issues of transitional justice, the controversy over the status of Compaore’s presidential guard, rumors of coup attempts. But survive it must because any derailment of this transitional process will no doubt lead to instability and a possible humanitarian crisis at the heart of West Africa, which will be a more fertile terrain for terrorist groups already operating in the region.

population of more than 15 million. A former French colony, it gained its independence in the 1960’s along with its neighbors such as Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Togo, Senegal, and Benin. As was usual in 1970’s and 1980’s in Africa, it took a turn for a Marxism-Leninism in the mid-1980’s with a group of young military officers led by Captain Thomas Sankara at its helm. In 1987, Sankara lost his life in a coup that brought Blaise Compaore, his right-hand man and second in command, to power. From that moment onwards, Burkina Faso started its long journey to liberalization, both politically and economically. Compaore’s three decade rule with explicit and implicit support from the West came to end in October 2014 when huge demonstrations of young people apparently led by well-organized civil society groups and opposition parties took place in the main cities. The main reason for this protest was Compaore’s willingness to modify the Constitution for a fifth term. A provisional government was quickly put in place to be in charge of the transitional process which should lead to presidential and legislative elections in October 2015. After almost ten months, this provisional government is sailing through troubled waters; its difficulties being so many that observers wonder if it will survive: high social demands, voting of controversial electoral rules, issues of transitional justice, the controversy over the status of Compaore’s presidential guard, rumors of coup attempts. But survive it must because any derailment of this transitional process will no doubt lead to instability and a possible humanitarian crisis at the heart of West Africa, which will be a more fertile terrain for terrorist groups already operating in the region.

First, let us remember that the October protest represents a break from a political system and practice that have outlived their usefulness: a political system marked by patrimonialism, cronyism and inefficiency. It is therefore not surprising that the youth thirsty of change has been the architect of this demand for change. Letting the provisional government boat sink will clearly imply, in the eyes of these young people, that they cannot rely on international system and its political values to have a say in the political chapter of their country, that democratic values daily praised by world leaders in leading newspapers are just empty rhetoric. And this will logically lead them to seek an alternative: getting themselves recruited by terrorist groups or any other kinds of fortune tellers.

In addition, if democracy peace theorists are right, it really makes sense to endorse the transitional process in Burkina Faso because the outcome of the process is no less than installing a political system that, for the first time, stands a big chance of being truly competitive. It cannot be otherwise because the political landscape has changed a lot: there’s a vibrant civil society dialogue of ideas, and political parties have started to compete on a level playing field. This has awakened young people, making them eager to participate in the elections and the political process. If the tide is allowed to turn against this trend, a new kind of authoritarian regime will step in with all the rigged elections, human rights violations that go with it. In his 10 July 2015 speech to the Nation, President Kafando warned of the likelihood of this chaos when he said: “If despite this pressing call, there are some adventurers, driven by evil forces, who would like to create chaos, they will answer for it before the tribunal of History and of course before the international criminal jurisdictions.” This implies more instability, more likelihood of terrorism and therefore less prospect of peace in the region which is already engaged in a political liberalization process, but has to cope with a formidable foe: terrorism.

Finally, democracy in an underdeveloped country is not only good for peace, it is also good for business. Of course, authoritarian regimes such as Compaore’s may first seem robust but in fact they are prone to instability which generally means unrest, upheavals which are very disturbing for business and investments. Newspapers have reported millions of dollars lost during this three day upheaval that led to Compaore’s resignation. For example, a Canadian-owned mining company called TrueGold stopped operating for months. So allowing competitive democracy to take root is no doubt the only way to robustness and stability of a resource-rich country that lies in a region which is strategically important in terms of the fight against terrorism.