By Jordan Morrisey

Slowing economic growth and increasing levels of debt painted a relatively stark economic picture for sub-Saharan African countries even before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the health and additional economic impacts it has wrought. New approaches to these concurrent challenges is needed to mitigate against the worst effects.

Debt levels across sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) remained relatively low until around 2012, when only a handful of SSA countries were carrying debt-to-GDP ratios above 50%. Up until this point, the absolute level of African debt had continued to grow, but economies in SSA also expanded, keeping debt ratios within reasonable bounds. More recently, economic growth in SSA has slowed. In 2016, for example, real GDP growth was less than 2% for all SSA countries and in particularly negative territory for oil-exporting states, like Angola and Nigeria, due to low and declining commodity prices for oil-exporting states. Many African countries continued to borrow even though declining growth threatened their ability to repay, which has led to rising debt ratios. At the end of 2017, average public debt in SSA was 57% of its GDP, an increase of 20 percentage points in just five years. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported in May 2018 that 15 of Africa’s 35 low-income countries are either in debt distress, meaning they cannot service their debts, or at high risk of debt distress. Due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, growth in SSA for 2020 was projected at –1.6%, the lowest level on record.

Some Factors to Consider

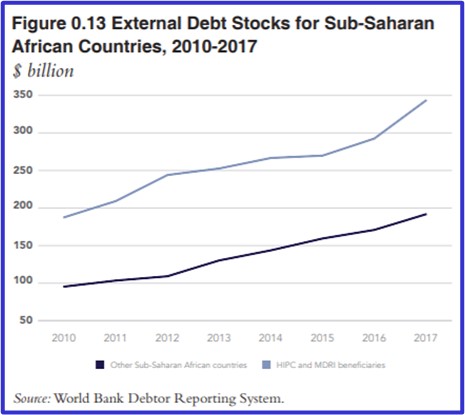

In particular, it is important to look at the changing composition of African debt, the capacity of governments to service their debt, and the role of China as an increasing lender to SSA. Rising concerns about debt sustainability did not slow debt accumulation in many of the poorer countries in SSA. The combined external debt stock of the 30 SSA countries that benefitted from debt relief under the Heavily Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) and Multilateral Debt Relief (MDRI) initiatives rose 11% in 2017, compared to 7% in 2016. The external debt stock of these countries has doubled since 2010 (see figure above).

A letter to President Joe Biden, initiated by the Jubilee USA Network and signed by over 260 organizations, calls for expanded debt relief and some cancellation.

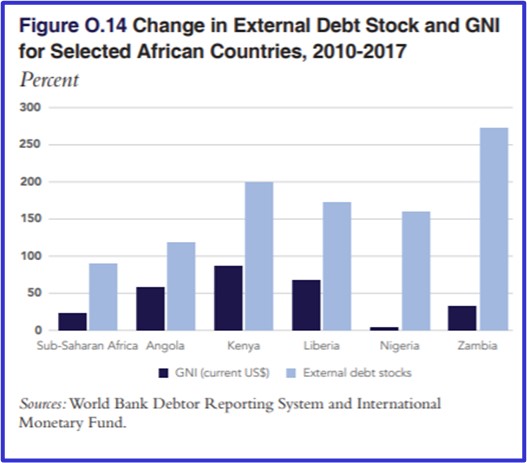

The rise in external debt stocks has also outpaced economic growth in much of the region. The ratio of external debt-to-Gross National Income (GNI) averaged 34.2% at the end of 2017, which was over 50 percent higher than in 2010. The GNI of SSA countries in U.S. dollars rose on average 23% between 2010 and 2017, while the combined external debt stock rose 90 percent over the same period. This is illustrated in the figure below.

The combination of higher levels of outstanding external debt and a hardening of overall lending terms due to the rising share of external debt owed to private creditors has been reflected in increased debt servicing costs. By the end 2017, one third of countries in the region had a debt service-to-export ratio above 10%, and in several SSA countries, including Cote d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gambia, Kenya and Zambia that ratio surpassed 15%.

A distinctive feature of the ongoing rising debt problem in SSA is the composition of debt. Countries are moving away from official multilateral creditors who come with stringent conditions and toward non-concessional debt with relatively higher interest rates and lower maturities. This trend raises concerns around debt sustainability given the possibility of higher refinancing risks—particularly for commodity-backed loans in the event of a commodity price shock—and foreign exchange risks. This debt is increasingly held not by governments but by a large number of private creditors, and interest rates are at market levels. Negotiating debt relief would no longer be a government-to-government affair.

Taking on debt is a strategy for securing revenue to pay for things and government borrowing to finance public investments is an essential part of any country’s macroeconomic toolkit. Over the last two decades, countries in SSA have used this option often, which has led to significant improvements in human development outcomes. For example, between 1990 and 2015, average life expectancy increased, infant mortality rates were halved, secondary school enrollment soared, and infrastructure gaps narrowed. These and other gains would have been impossible without pragmatic spending of borrowed resources. Africa’s increasing public-debt burden, however, means higher interest costs, which divert resources from education, health care, and infrastructure to increasingly pay for the servicing of that debt.

COVID-19’s Impact

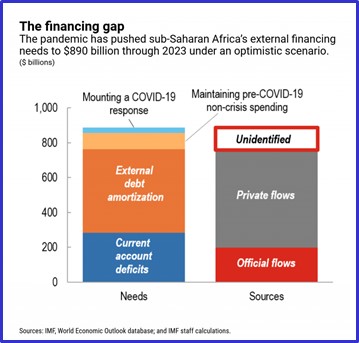

While developed nations are using the full-range of macroeconomic tools to mitigate the impact of the pandemic, developing countries in SSA have little monetary or fiscal space to cushion the blow of the systemic shocks cause by COVID-19. Export revenues are falling and access to external finance is drying up, while domestic responses to the health threat will negatively affect tax revenues, which are already insufficient. In the face of a major and truly exogenous shock, governments in many low and middle-income countries must contend with soaring spending needs, declining revenues, and insufficient resources to borrow from to fill this gap. As a result, their ability to meet their existing debt commitments is in serious jeopardy, as can be seen in the figure below.

Calls for debt cancellation, restructuring, and payment moratoriums are growing. A letter to President Joe Biden, initiated by the Jubilee USA Network and signed by over 260 organizations, calls for expanded debt relief and some cancellation. Even traditional skeptics of the efficacy of foreign aid, like economist Dambisa Moyo, have shifted their positions in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moyo has called for a modern day “Marshall Plan” for Africa in response to COVID-19. Modelled after the big aid package that the U.S. provided to European countries after World War II, this plan would provide an opportunity to expand Western influence in the region, especially at a time when China has staked out a position as the “pre-eminent geopolitical force in Africa.” This could be an opportunity for the U.S. to re-engage with SSA and gain an ideological and commercial edge over China, mirroring how the U.S. was motivated to create the original Marshall Plan to prevent Europe from aligning with the Soviet Union. In the spirit of the stimulus approach, used in places like the U.S. and Hong Kong, Moyo advocates that donor countries should consider direct cash payments to African households. “The beauty of a direct-transfer approach is that it mitigates the risk of funds being illicitly diverted,” Moyo explains, “as billions in aid have been before, despite all the ‘conditionalities’ that are regularly imposed to prevent this.” This approach could leverage the robust, existing payment infrastructure that makes peer-to-peer cash transfers via mobile phones so popular in SSA, such as with M-PESA in Kenya.

The author is the Deputy Director for Global Operations at AMP Health, a public-private partnership which supports governments in sub-Saharan Africa to build visionary and effective public sector teams, and is hosted by the Aspen Institute. He is also pursuing a Master of Science degree in Development Management at American University’s School of International Service.